From The New York Times:

How does a person get to be the boss? What does it take for an ambitious young person starting a career to reach upper rungs of the corporate world — the C.E.O.’s office, or other jobs that come with words like “chief” or “vice president” on the office door?

The answer has always included hard work, brains, leadership ability and luck. But in the 21st century, another, less understood attribute seems to be particularly important.

To get a job as a top executive, new evidence shows, it helps greatly to have experience in as many of a business’s functional areas as possible. A person who burrows down for years in, say, the finance department stands less of a chance of reaching a top executive job than a corporate finance specialist who has also spent time in, say, marketing. Or engineering. Or both of those, plus others.

However, there is still such a thing as too much variety: Switching industries has a negative correlation with corporate success, which may speak to the importance of building relationships and experience within an industry. Switching between companies within an industry neither helps nor hurts in making it to a top job.

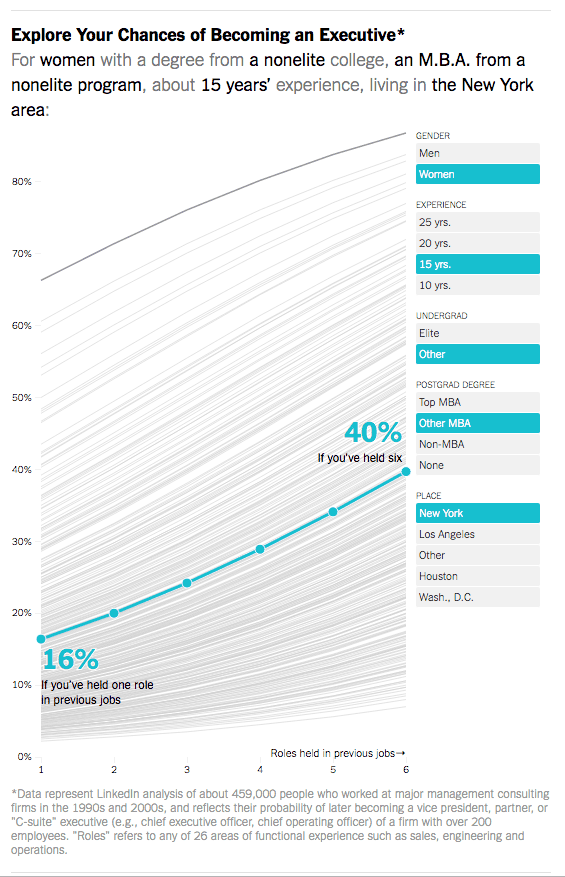

These are some of the big findings in a new study of 459,000 onetime management consultants by the social network LinkedIn. Experience in one additional functional area improved a person’s odds of becoming a senior executive as much as three years of extra experience. And working in four different functions had nearly the same impact as getting an M.B.A. from a top-five program.

This interactive graphic shows how different traits affected a former consultant’s likelihood of ending up as a top executive of a midsize or large company.

Similarly, Burning Glass, a firm that scours millions of job listings to detect labor market trends, has found a surge in demand for what it calls hybrid jobs, incorporating expertise in, for example, both technology and finance. And researchers have found that M.B.A. holders with a variety of experiences get more offers and higher bonuses from investment banks than those with narrower experience.

While some of this might sound intuitive, and top executives have always needed to have grounding in a range of specialties, huge collections of data about individuals have only recently made it possible to analyze in such detail what traits and experiences seem to predict success in the job market.

In effect, the increased ability to collect and analyze such troves of data raises the possibility that in the future we’ll be able to better understand what types of education the workers of the future most need, how companies can best recruit future star performers and how individuals can position themselves to benefit from shifts in what skills the modern economy most rewards.

There is a lot of work to be done to get to that point. But this early evidence suggests that success in the business world isn’t just about brainpower or climbing a linear path to the top, but about accumulating diverse skills and showing an ability to learn about fields outside one’s comfort zone.

“Work used to be much more hierarchical, and in many instances rote,” said Gary Pinkus, McKinsey & Company’s managing partner for North America. “You could build a nice career within any particular function by taking on more responsibility within that specialty. But if you look at most companies now, work has become incredibly cross-functional.”

Once upon a time, Mr. Pinkus said, an operations manager might be laser-focused on making a factory work efficiently. Now to be great at that job — and earn a promotion to vice president or beyond — that manager had better also understand how the factory’s inventory procedures tie in with the company’s sales and marketing strategy, and any tax laws affecting inventory management, while assuring the reliability of the supply chain.

The manager had better also be adept at using the technology that links all that information together.

Marc Andreessen, the prominent venture capitalist, has gone so far as to call this the “secret formula to becoming a C.E.O.” The most successful corporate leaders, he wrote, “are almost never the best product visionaries, or the best salespeople, or the best marketing people, or the best finance people, or even the best managers, but they are top 25 percent in some set of those skills, and then all of a sudden they’re qualified to actually run something important.”

The Nonlinear Career

George Kurian was a young engineer at Oracle in the early 1990s, helping build database software. Then a manager pushed him to break out of his software engineering silo and see what it was like to deal with potential customers.

That’s when things got interesting.

“I had built a set of technologies I thought were groundbreaking,” he recalled recently. “I went into this meeting expecting I was going to bring my engineering skills and wow this customer with our amazing technology. She asked, ‘Who built this piece of software?’ and I said, ‘Yes, that was me.’ ”

Her next comment, though, wasn’t what Mr. Kurian expected at all.

“She said, ‘You have no idea what my day looks like,’ ” Mr. Kurian recalled.

The software didn’t solve the problems the customer actually had. The valuable lesson for the young engineer? Work that seems impressive on an engineering level isn’t always what will most satisfy paying clients.

As a product manager, Mr. Kurian added sales and marketing and team management to his engineering background. He later did a stint as a strategy consultant, which he recalls as a crash course in quickly synthesizing information about unfamiliar situations. He considers the combination of all of these areas a key to his path to becoming chief executive of NetApp, a data storage company with a $10 billion market value.

He represents one common way to collect experience across functions: Within a larger company, pursue opportunities that are adjacent to, yet different from, existing expertise.

“People tend to think of their career as a linear progression,” he said. “I think having a nonlinear career progression helped me.”

The LinkedIn data doesn’t address causality. Did Mr. Kurian advance to a C.E.O. job because he gained experience across different functions, or did the traits that led him to take on a variety of assignments in his career also lead to his being an attractive candidate for top jobs? And the former consultants who created detailed LinkedIn profiles may be different in some systematic way from those who did not, which would distort the results.

Beyond the results on job functions, the data from LinkedIn shows some trends for which the explanations aren’t completely obvious. For example, former consultants who lived in New York or Los Angeles had higher odds of ending up with a top job than people in other large cities like Washington or Houston. A former management consultant with 15 years of work experience in six different functions and an M.B.A. from a top school had a 66 percent chance of becoming a top executive if he lived in New York compared with a 38 percent chance in Washington.

But regardless of how exactly the cause and effect works and how the consultants analyzed might be different from others who weren’t included in the sample, there is evidence that more top jobs in business require an ability to meld knowledge from different fields.

In a 2014 survey of 2,100 chief financial officers by Robert Half Management Resources, 85 percent said their role had expanded beyond traditional accounting and finance-related work over the preceding three years, most commonly into human resources and information technology.

And two business school professors, Jennifer Merluzzi of Tulane and Damon J. Phillips of Columbia, studied hundreds of graduates of an elite M.B.A. program who went into investment banking. The people who were specialists — who had focused only on banking in the past — received fewer offers and lower starting bonuses than those who had worked across various specialties.

Burning Glass found a 53 percent rise in the number of openings for hybrid jobs requiring both technological and business acumen from 2011 to 2015, for jobs like product management and marketing analytics.

“The common theme that we see in the jobs that are the fastest-growing and have the highest value for employers and job seekers is this set of jobs that require a mix of skills that don’t tend to ride together in nature,” said Matthew Sigelman, the chief executive of Burning Glass.

Entrepreneurial Options

There are ways a young person can gain experience across functions that aren’t a matter of taking on different assignments within a big company. Marla Malcolm Beck embodies this other, more entrepreneurial path.

Ms. Beck worked in consulting right out of college in the mid-1990s, then studied at Harvard Business School and worked briefly in private equity. But she found the work unfulfilling, and in 1999 started Blue Mercury as an online seller of beauty products. Soon after, as the dot-com boom turned bust, the company pivoted toward physical stores.

Ms. Beck built Blue Mercury into a 109-store chain. Macy’s acquired the company for $210 million last year, and she remains its chief executive.

In her days as a consultant she had worked on projects like figuring out the pricing of mutual funds and re-engineering the claims process for an insurance company. As a retail C.E.O., she essentially trained herself across the various functions it takes to make a retail business work: inventory and supply chain management, information technology systems and everything else.

She acted as the company’s chief financial officer even as it grew, entrusting routine accounting to a controller but doing the strategic work of forecasting and financial modeling herself. Some fields have come easier to her than others. “I think I’m almost too logical for some of the emotion around marketing,” she said.

Her approach has been to break down each of these new areas in which she had to immerse herself as a start-up founder the way she once did in unfamiliar fields as a consultant.

“What I really learned from those experiences was how to break down even the most complicated processes into their most minuscule components,” she said. “It’s an approach that you can use to tackle any process in any organization.”

In hiring at Blue Mercury’s corporate headquarters in Washington, she has focused less on traditional retail industry experience and more on people who have a comfort with engineering processes, skills they can apply to whatever urgent task arises.

In other words, she didn’t become chief executive by getting loads of experience across functions. Rather, she took some core analytical skills and used them to learn to develop experience in those functions as she went.

There are some parallels with programs that the biggest companies have long operated to deliberately rotate promising young executives across different divisions, to ensure that as they hit midcareer they have broad experience. The challenge can be to replicate that kind of experience even in a world where few people sign on with a single large employer for decades.

To be a C.E.O. or other top executive, said Guy Berger, an economist at LinkedIn, “you need to understand how the different parts of a company work and how they interact with each other and understand how other people do their job, even if it’s something you don’t know well enough to do yourself.”

Out of the Comfort Zone

Kai Monahan embodies a third pathway through different specialties into top executive jobs. He didn’t start his own company, like Ms. Beck, or gradually add different layers of experience that were adjacent to his previous job, like Mr. Kurian.

Rather, at some key junctures he jumped headlong into an entirely new function. In 1999, he left the (now defunct) accounting and consulting firm Arthur Andersen, where he had worked on projects to transform businesses, for Ernst & Young, where he focused on risk management, a less sexy field that became more in demand after the accounting scandals at Enron and others starting in 2001. In 2008, he joined Nationwide Insurance as its chief audit executive, before quickly moving out of the back office and into selling financial products to consumers in an operational role. He became president of Nationwide’s mortgage business in 2014.

It helped that he had an early mentor who encouraged him to take risks in his career by taking on jobs he was unfamiliar with — and bosses willing to take a chance on assigning him jobs he wasn’t qualified for on paper.

After all, if you assign, say, an accounting specialist to run a logistics operation, there’s a chance that person will fail. What’s best for the employee who wants to get broad experience to help climb the ranks may not be what is best for the employer who wants deeply experienced people in every job.

“There’s comfort in familiarity,” Mr. Monahan said. “Leaders can be reluctant to hire someone who doesn’t have directly applicable experience. That’s still a mind-set that is fairly prevalent.”

But how does one navigate into sharply different functional specialties while also dealing with new colleagues and a new organizational culture? “If you’re in your comfort zone, it’s very easy to stay in your comfort zone,” said Paul McDonald, a senior executive director at the recruitment firm Robert Half International.

“What was critical for me in going into new functional areas was breaking that habit of feeling like you have to know it all,” Mr. Monahan said. “When you’re honest with yourself and with others in terms of your need for their support and involvement, generally people are willing to share with you what they know and help you be successful.”

In other words, the path to the executive suite may be long and winding, and include stops in many different types of specialties. But the key to navigating it is being able to learn from others all along the way.

By Neil Irwin @Neil_Irwin SEPT. 9, 2016, New York Times